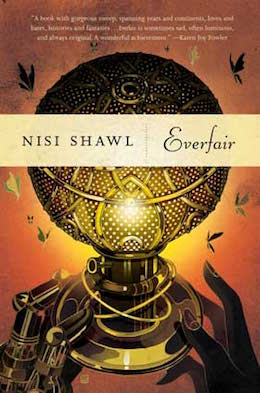

Nisi Shawl’s Everfair is a wonderful Neo-Victorian alternate history novel that explores the question of what might have come of Belgium’s disastrous colonization of the Congo if the native populations had learned about steam technology a bit earlier. Fabian Socialists from Great Britain join forces with African-American missionaries to purchase land from the Belgian Congo’s “owner,” King Leopold II. This land, named Everfair, is set aside as a safe haven, an imaginary Utopia for native populations of the Congo as well as escaped slaves returning from America and other places where African natives were being mistreated.

Told from a multiplicity of voices, Everfair manages to turn one of the worst human rights disasters on record into a marvelous and exciting exploration of the possibilities inherent in a turn of history. Available September 6th from Tor Books. Read an excerpt below, and check out another sneak peek at the novel at the Tor/Forge blog!

Fifty Kilometers out of Matadi,

Congo, July 1894

To Jackie Owen, the way seemed arduous and long. During this time—miscalled “the dry season”—the Congo sweltered in humidity comparable to the Gold Coast’s. The wet air corroded every thing. The rank vegetation smoked almost as much as it burned when fed into the expedition’s small boilers.

Chester and Winthrop had had the right of it; their steam bicycles were destined for greatness. The traction engines did well enough over terrain recently cleared for construction of a railroad. But that would end. The broad way they traveled would narrow to a mere footpath ahead, up where the Mah-Kow coolies had their camp.

And for now, the ground continued to rise.

Jackie turned to look back along the pro cession following him. Line of sight ended after only a dozen men, but his elevation allowed him glimpses of those farther behind.

Beside the three heavy traction engines, the baker’s dozen of bicycles valiantly pulled more than their own weight. English workers and natives took turns shepherding the narrow, wheeled baskets trundling in the bicycles’ wakes. Clouds from their boilers diffused into the mist spiraling up from the jungle’s relentless green.

But why was that last machine’s plume so much thicker than the rest? Hurriedly he signaled a halt and went back down to investigate.

Winthrop was there ahead of him. “The regulator’s faulty, Mr. Owen.”

“Is it possible to repair—”

“It must be replaced. I’ll take care of it.”

“We have a spare one?”

The stocky Negro nodded at the first wheeled basket in the steam bicycle’s train. “Several.” He leaned forward and began to unpack a wooden chest. “I’ll finish to night.”

Jackie continued to the end of the halted line, explaining the problem. As he had expected, the natives received the news with stoicism. Since the expedition didn’t require them to kill them.selves with the effort of hauling its luggage up to the river’s navigable stretches, they found no fault in however else things were arranged.

The women were another matter. The Albins’ governess, Mademoiselle Lisette Toutournier, still held the handlebars of the steam bicycle she had appropriated at the journey’s outset. “How is this? We lack at least two hours till darkness and you call a stop?” For some reason that escaped him, the French girl challenged Jackie at every opportunity.

Daisy Albin’s anxiety was understandable: she had left the children behind in Boma with their father, Laurie. The sooner the expedition reached their lands beyond the Kasai River, the sooner she would be able to establish a safe home for them there. “Are you sure you couldn’t find a more inconvenient camping ground?” Her rueful grin took away her words’ sting.

Jackie reconsidered their surroundings. The considerable slope was more than an engineering obstacle; it might indeed prove difficult to sleep or pitch a tent upon.

“If we proceed with less equipment should we not meet with a better location? Soon?” Mademoiselle Toutournier’s wide grey eyes unnerved him with their steady gaze.

Jackie shuddered at the thought of the women striking out on their own, meeting with unmanageable dangers such as poisonous snakes or colonial police. He had opposed their presence on the expedition as strongly as it was possible to do without making a churl of himself or intimating that they were somehow inferior to men. That would be contrary to the principles upon which the Fabian Society was formed.

The third woman, Mrs. Hunter, approached, accompanied by Wilson and by Chester, the other of her godsons. “I would like to introduce a suggestion…”

Jackie steeled himself to reject an unreasonable demand of one sort or another—a night march? Several hours’ retreat to a site earlier passed by?

“Perhaps we would do better not to sleep at all? Reverend Wilson and I have been thinking to hold a prayer meeting, a revival, and there is no time like the present. We might easily—”

Jackie paid no heed to the rest of the woman’s argument. Yes; the idea had its merits. But proselytizing a religion?

“We are part of a socialist expedition.” He could tell by Mrs. Hunter’s expression that he had interrupted a sentence. He went on nonetheless. “If I put the issue to a vote, do you think a prayer meeting will be the choice of the majority?”

“I—I believe most of my countrymen to be decent, God-fearing Christians.”

“These are your countrymen!” Jackie swung one arm wide to indicate every one in their immediate vicinity and beyond. “Not only those who came with you from America, but all now on the expedition—Catholics! Skeptics! Atheists! Savages as well—do you not count your African brothers’ opinions as mattering? Shall we canvass their number for a suitable spokesman to explain to us the spirits lodged in the trees and bushes?”

“I venture to—”

“Yes, you venture, you venture forth to a new life. A new home. A new country, and new countrymen.” If only he could bring the colony’s expedition to some sort of coherence, to unity; then the whites’ sacrifice would mean so much more. What would that take?

Mrs. Hunter turned to Wilson. “But our aim is to build a sanctuary for the soul, isn’t it? As well as for mere physical victims of the tyrant’s cruelty?”

Wilson nodded. “Yes, we must consider all aspects of our peoples’ well-being.”

What had Jackie expected? The man was a minister, after all, though he had agreed to the Society’s project of colonization as Jackie, their president, had extended it. In the end, the plan was for a series of gatherings up and down the trail. Mrs. Hunter decided she and Wilson would harangue all three parties in turn. Each was centered loosely around one of the traction engines’ boiler furnaces.

They began with their “countrymen,” the Negroes grouped together at the pro cession’s rear (Jackie had done his utmost to integrate the expedition’s various factions, but to no avail). The Christians’ message, from all he could tell, contradicted none of the Fabian Society’s ostensible reasons for crossing the Kasai River, only casting them in the light of a mandate from Heaven. He listened a short while to what Mrs. Hunter and Wilson preached. Then he preceded them to the British and Irish work.men clustered around the middle boiler, whose participation in the Society’s experiment he’d insisted on—gambling that, in the eyes of the audience he had in mind, the workmen’s race would trump white Europeans’ objections to their class.

Though for many years an office-holder in the Fabian organization, Jackie Owen was no public speaker. As an author, the written word was what he normally relied on and, he hoped, what would soon attract the attention this project had been set up to generate.

Given the circumstances, he did his best. He made sure the firelight fell on his face. “Practical dreamers,” he said. “That’s what we are. Dreamers, but realistic about it. Heads in the clouds, but our feet on the ground.” He saw their eyes glittering, but little else.

“You’ve come this far. Abandoned your homes, left your wives behind.” Well, most of them had. “Trusting me. Trusting in your own right hands, the work you do. The work that has made the world and will now make it anew.” He paused. What else was there to say? Nothing that could be said.

In the distance behind him he heard music. Church songs. Invoking primal reactions with pitch and rhythm—how could he fight that? He couldn’t.

But the men listening: maybe they could. “If I stood here all night, I wouldn’t be able to convey to you one half of what I aim for us to accomplish in our new home, liberated from the constraints of capitalism and repressive governments. I know many of you are eager to share your own ambitions for our endeavour, and I invite you to do so—now is the time!” He called on a workman whose name he remembered from a recruitment meeting. “Albert, step up and tell your fellows about that flanging contraption you’re wanting to rig up.”

“Me?”

“Yes—yes, you, come here and talk a bit—”

Albert obliged, stepping into the furnace fire’s ruddy glow with his jacket and shirt wide open to the heat and insects. Self-educated, of course. Still, he had some highly original ideas on how to revise manufacturing processes for an isolated colony… but as his eyes adjusted to the darkness beyond the boiler’s immediate vicinity, Jackie saw the audience’s interest was not much more than polite. Music exercised its all-too-potent charms. Heads nodded, hands tapped against thighs, necks and shoulders swayed, and he thought they’d be singing themselves at any moment. The song ended before that happened, though. Albert finished his discourse in silence and stood in the furnace’s light without, evidently, any idea of what next to do.

“Thank you, Albert,” said Jackie. This elicited light applause and gave Albert the impetus he needed to find and resume his old place among the onlookers.

Just as Jackie was wondering who next to impose upon for a testimonial, the music began again. No, not again, not the same music from the same source. This came from the other end of their impromptu encampment, from the head of the pro cession. Where the natives had gathered by the boiler furnace of the first traction engine. Where Mademoiselle Toutournier had insisted on remaining, with Mrs. Albin insisting on remaining with her.

A lyric soprano sang a song he’d never heard that was, somehow, hauntingly familiar from its opening notes:

“Ever fair, ever fair my home;

Ever fair land, so sweet—”

A simple melody, it was winning in its self-assurance, comforting, supportive, like a boat rowed on a smooth, reflective sea. Then it rose higher, plaintive in a way that made one want to satisfy the singer:

“Ever are you calling home your children;

We hear and answer swiftly as thought, as fleet.”

A chorus of lower voices, altos, tenors, and baritones, repeated the whole thing. Then the earlier voice returned in a solo variation on the theme:

“Tyrants and cowards, we fear them no more;

Behold, your power protects us from harm;

We live in freedom by sharing all things equally—”

The same yearning heights, supported by an inevitable foundation. A foundation that was repeated as the resolution necessary for the verse’s last line:

“We live in peace within your loving arms.”

He was staring through the darkness at the little light piercing it ahead. So, he felt sure, were all those with him. The chorus repeated, graced this time by—bells? Gongs? Singing swelled around him now and he joined it. A second verse, and a third one, and by then he was on the edge of the circle with Daisy Albin and the lead engine at its center. She sang. She it must be who had penned the words, taught them by rote, composed the music in which the entire expedition now took part. The bells and gongs revealed themselves to be pieces of the traction engine, struck as ornament and accent to the anthem’s grave and stately measures.

The anthem. This was it: their anthem. Before they’d even arrived home, they sang their nation’s song. And knew its name: Everfairland. This would be what Leopold endangered, what could rouse all Eu rope to revenge it if it were lost.

Mrs. Albin had stopped. The chorus continued. Jackie made his way through the happy, singing throng to clasp and kiss her hands.

Excerpted from Everfair © Nisi Shawl, 2016